A Concise History Of the Dinka

Written by Bior Malual

The Dinka today are a notable ethnic groups living mainly in the region of East Africa in the country of South Sudan. Their population is close to around 4.5 million people and are known mainly for their pastoral actives, along side with being one of if not the tallest ethic group in the world. This ethic group produced the NBA’s tallest player Manute Bol, standing at a staggering 7’7 feet tall. Besides basketball, the Dinka and as well as other South Sudanese ethnicities are also known for dominating the modeling industries with famous models such as Anok Yai, and Adut Akech. These remarkable accomplishments go say that the people of this ethnic group are a great people, however much is not very known about their origins. Which is what I will be discussing throughout this reading.

Most of what is known about Dinka history has to do with the Sudanese civil wars, fought from 1955-1972, and then again from 1983-2005. Although this is an Important and integral part of the Dinka history, and the history of South Sudan as a nation, not much is really known beyond this.

Oral Traditions:

Oral traditions are always and important aspect of African culture, especially in those communities without a written language, because it is how a history of a people os preserved in absence of any written language. Unfortunately however, they aren’t considered the most reliable source of information, after a certain amount of years and generations, they are considered pretty much unreliable. This is because scholars define the as a “The Telephone Game”.

When it comes to the Dinka, it isn’t very different, in this paper, I will be discussing the oral traditions of the Dinka, about coming from the North, and more importantly, I will be reviewing the evidence that supports the claim of a migration story of an origin in the Gezira region of modern day Sudan. However, oral tradition can be used in light to, or in comparison with multiples fields of study in the process of helping us understand the past, such as linguistics, archeology, genetics, and etc….

Early History

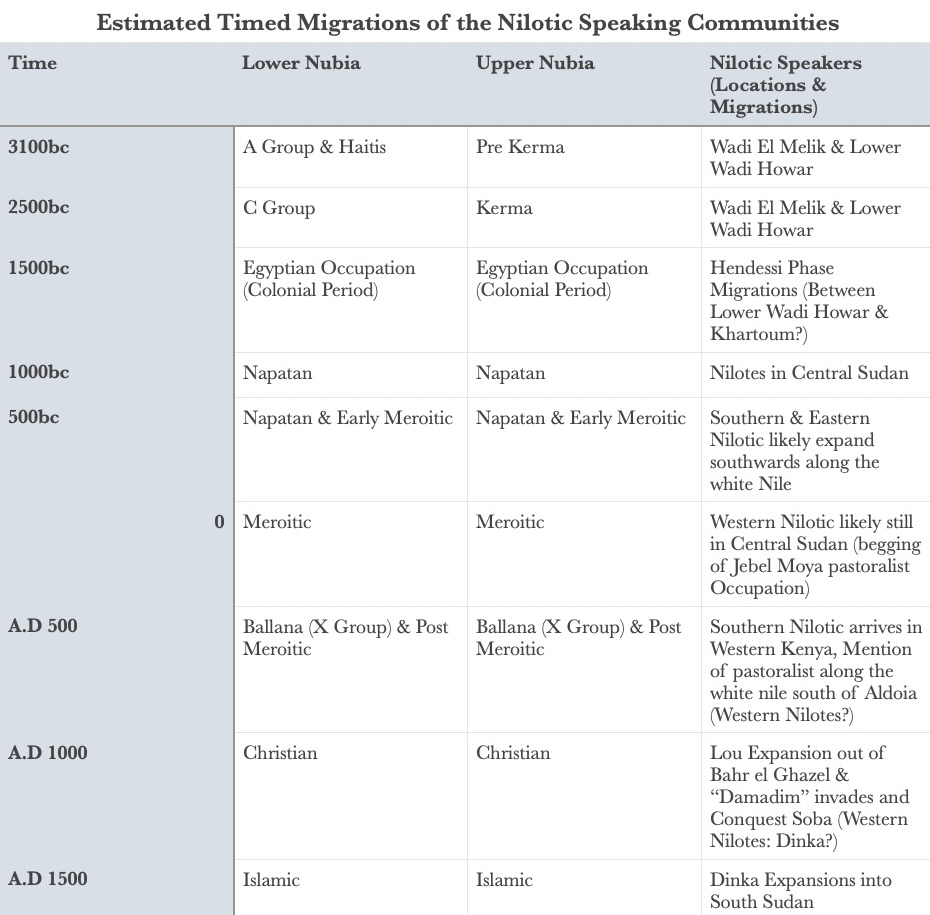

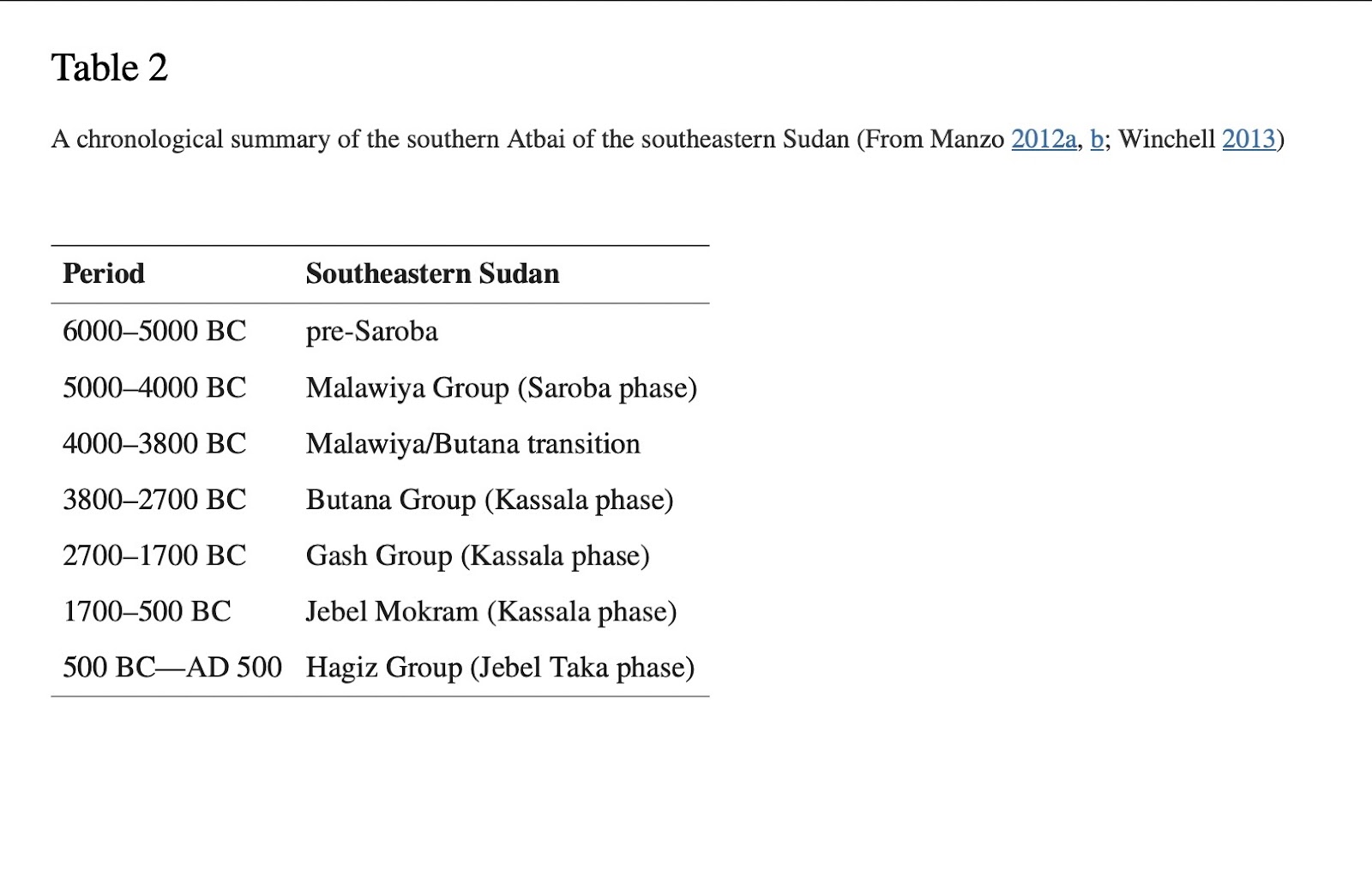

During the neolithic Bronze Age period, communities ancestral to much of the eastern Sudanic stock started to migrate out of a region of North Western Sudan from a place known as the “Wadi Howar” or “Yellow Nile”. Fromm this place, these people entered into Nubia, and its surrounding areas. Of these groups, one of them were the Nilotic peoples speakers), who interacted with some of the inhabitants of Nubian Kerma culture, living primarily in the Lower Wadi Howar & Wadi el Melik, bordering on the area of the Nile between the 3rd & 4th cataracts until a migrations between 2000-1000bc, moving towards the Central Sudanese region around Khartoum and the Gezira later by the end of these migrations (from an event known as the “Wadi Howar Diaspora”). Later on we see that archeological sites in the Gezira during the Meroitic (300bc-300ad) period show affinities with Nilotic cultures, which are evidence by their social economic practices such as semi nomadic pastoralism, dental tooth evulsion.

The ancestors shared by the speakers of the extant Nilotic and Surmic languages originally occupied the area through which the Lower Wadi Howar and the Wadi el Milk pass. The Wadi Howar as a whole was part of the diffusion area in which the Eastern Sudanic languages presently spoken in the north acquired the typological features they share with members of other Nilo-Saharan groups, for instance Masalit, Fur and Beria. Interactions in the Central Sudanese Kordofan region during the later southward migrations provided the context in which the other set of typological traits became a characteristic of the Eastern Sudanic languages ancestral to those currently spoken in the south. These contacts most likely also led to language shifts and the absorption of groups speaking typologically different languages.

Trade with Kerma:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285386959_Hope_your_cattle_are_well

(Page 82)

Quote:

Increasing aridity during the fourth millennium BC and corresponding changes in the ecosystem in the Lower Wadi Howar (Pöllath and Peters 2007: 65) probably stimulated the growing importance of cattle in economic and social life, and therefore led to the adoption of features such as pits previously known only west of Jebel Rahib in the Leiterband Complex. The recurrence of cattle and the appearance of elements of cattle cults, such as cattle burials, can then be seen as a social response to environmental changes (di Lernia 2006). However, the sites of the late fourth and third millennium BC in the Lower Wadi Howar cannot simply be incorporated into the Leiterband Complex as they show originality reflected especially in the different pottery design styles present. Besides Leiterband patterns, incised herringbone patterns are present which clearly indicates strong contact with the A-Group and pre-Kerma culture in the Nubian Nile Valley around the third and second Cataracts (Keding 2000: 92; Jesse 2006: 49). Affiliation with the Nile Valley is also reflected in the archaeozoological record: the cattle bones found in the Lower Wadi Howar overlap in size with those of the Egyptian and Sudanese Nile Valley (cf. Pöllath and Peters 2005; Jesse et al. 2007), indicating the exchange of livestock and/or the adoption of efficient strategies of husbandry as they had been developed, for example, in Egypt since the Old Kingdom (Laudien 2000: 102-8). The obvious mixture of different culturaltraits in the Lower Wadi Howar led to the development of local forms of cattle-centred behaviour at the periphery of the Leiterband Complex.

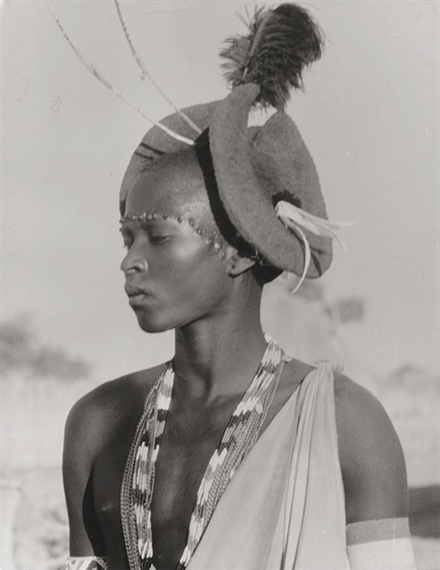

What can be seen when comparing the nilotic tribes of Southern Sudan such as the Dinka, there are many commonalities they share with the ”Nubians” that are illustrated in these Egyptian period (which are all mostly dated to the New Kingdom period during the Egyptian colonial period in Nubia) such as basic things as skin color, hair styles, tribal markings, lifestyle, and even clothing. Hairstyles such as blonde or yellowish hair, leopard skin clothing, forehead tribal markings similar to that of the Nuer, and dark skin may be distinguishing factors to help us identify ancient Nubian populations likely from deeper with in Nubia in comparison to other Nilo Saharan populations in Nubia, such as the Meroitic speakers, who likely lived in closer proximity to Afro Asiatic speakers and may have hairstyles and culture more similar to the previous Cushitic speaking cultures of Nubia and as well as Egyptian cultural influence. This was due to their migration to the Kerma area after the Wadi Howar Diaspora as reported by linguist and Egyptologist Claude Rilly. During this time period, the Nilotic speakers would’ve still been in Nubia, likely in its South western reaches, between the Lower Wadi Howar and Khartoum, and some of the North Eastern most places of the Kordofan region. Populations that resemble Dinka and Nuer populations can possibly be seen as ancestral to these populations when taking all of this account.

Another added note is that these location may pose a link with the ancient land of Yam, mentioned in ol kingdom Egyptian records. This is very speculative & I dont have much at my hands to prove this beyond any reasonable doubt, but I will say that these observations are noteworthy. I will leave some maps up to compare locations.

|

Postulated routes for Harkhuf's second journey (filled line) and third journey (dotted line), with possible locations of Egyptian toponyms. Modified Google Earth Image, © 2012 Google. |

The Split of the Nilotic Languages:

A key aspect of the reconstruction of the Dinka past is understanding the Nilotic languages, concerning when and how they split. This will help us theorize locations and migration patterns. Through researching & attempting to reconstruct the split what the split of Nilotic language groups I came up with the following dates. Proto Nilotic languages are maintained theorized too have been spoken during the 3rd millennium bc (3000-2000bc), assuming that each of the 3 branches took mellenia to separate from each other, we'd then have Proto Southern Nilotic being spoken in the 2nd mellenum bc (2000bc -1000bc) who were commonly believed to have arrive in Kenya by 500bc (recently dna testing from pastoral neolithic & Iron age dna as well as other evidences prove that the southern nilotic migration into Kenya actually happened closer to 500ad which is roughly a thousand years later due to dna findings cutting the links between teh Southern nilotes and the Elmenteintan culture which was found to be just Southern Cushitic in actuality through dna testing). After this we'd then have Proto Eastern Nilotic in the 1st millennium bc (1000bc - 0 A.D). And then finally Proto Western Nilotic during the 1st millennium A.D (0ad -1000ad). Proto Western Nilotic may have been spoken in the Gezira or somewhere around that area in central Sudan, as we will see in the next section evidence form Nilotic like culture during this same time period, during the Meroitic period. It is also believed that the Proto Western Nilotes were the most northerly of all of the Nilotes, staying much closer to the Proto Nilotic homelands. Which other more recent research suggest was the Lower Wadi Howar region & central sudanese regions. My current understanding leads me to speculate that Proto Western Nilotic may have been spoken between 1000bc-500bc. Much later than Ehrets suggested 2000bc which is much earlier. But all of this is throned considering the migrations of Western nilotic speakers, including archeological, linguistic, and documented resources, but as well as considering the fact that some western nilotes still live in the southern reaches of the Gezira region today, including Dinka, Burun, and Shilluk.

Methodology:

https://academic.oup.com/jole/article/5/1/17/5688948#201331000

Quote:

The sum of the branch lengths from any extant language to the root of the tree must be the same, and this sum represents the age of the protolanguage. For example, Fig. 1 represents a hypothetical language family, which is 4,000 years old (branch lengths are in units of millennia).

(Page 92)

Quote:

After ca. 2000 B.C. the proto-Nilotes diverged into three separate societies--the River-Lake or western Nilotes evolving on the north of the proto-Nilotic homeland areas. the Highland or Southern Nilotes to the southwest, probably off the southern edges of the Ethiopian plateau, and the Eastern or Plains Nilotes to the southeast. The second grouping thus moves off the stage of our early history of the Congo-Nile watershed region, while the Eastern Nilotes gained, to the contrary, a redoubled importance through their spread into the edges of Central Sudanic speaking territory along the east of the Nile. At the same time, we can see from the appearance of complex cultivating terminology in each Nilotic branch that grain crops were beginning to develop into more important Nilotic subsistence pursuits.

After ca. 2000 B. C. the proto-Nilotes diverged into three separate societies--the River-Lake or western Nilotes evolving on the north of the proto-Nilotic homeland areas, the Highland >r Southern Nilotes to the southwest, probably off the southern edges of the Ethiopian plateau, and the Eastern or Plains Nilotes to the southeast. The second grouping thus moves off the stage of our early history of the Congo-Nile watershed region, while the Eastern Nilotes gained, to the contrary, a redoubled im- portance through their spread into the edges of Central Sudanic speaking territory along the east of the Nile. At the same time, we can see from the appearance of complex cultivating terminology in each Nilotic branch that grain crops were be- ginning to develop into more important Nflotic subsistence pur- s u i t s . Admittedly, Central Sudanic agency in t h i s development is not overwhelmingly attested, but some individual pieces of evidence suggest important Central Sudanic influence on at l east the Eastern Nil otes . A striking example is proto-Teso- Masaian (Eastern Nilotic) *-tapa which means "porridge."l7

The Gezira

Important historical region in Sudan, home to multiple kingdoms, located just South of the Nubian Nile Valley. It is going to be an important region when it comes to rediscovering the Dinka past. As we will see evidence for occupation of this region, both through archeological, and documented records. This place may also be very well where the Proto Western Nilotic languages we spoken around 0 A.D.

Alodia Kingdom:

The kingdom of Alodia was one of the 3 Christian medieval kingdoms that dominated Nubia. It was a multicultural state that succeeded the kingdom of Kush which fell around the 4th century A.D. And was 1st mentioned a few centuries later, around 569 A.D described by John of Ephesus as a kingdom on the brink of Christianization. Other than this account, there is also mention of an Alodian slave girl being sold in Byzantine Egypt during the from later in the same century. It is relevant because much of the territory that the kingdom controlled may have formally been held by the Nilotic speaking peoples. It also should be noted the migrations and expansions during the middle age from many Western Nilotic communities seem to coincide with the time period of the fall of this kingdom, and the collapse of Christian Nubia as a whole.

http://www.medievalnubia.info/dev/index.php/John_of_Ephesus

(Page 14)

Quote: (Christianization)

When the people of the Alodaei knew that the Nobadae had been converted, their king sent a letter to the king of the Nobades, asking to send him [the bishop] who had taught and baptised the Nobades, that he might instruct and baptise also the Alodaei. But Longinus had received a letter from Alexandria and he had Immediately set out for the country of the Romans [i.e. Egypt] and had fallen into all the trials we described above<ref>Chapters IX-X [not reported here].</ref> and It was only after great labour and many efforts that the king of the Alodaei<ref>See note 7.</ref> could send a delegation to take him back to [p. 15] their, country. Then the Alexandrians<ref>John means the Melkites who were ruling Alexandria of Egypt with the support of the emperor of Constantinople.</ref>, as if moved by satanic envy, were striving to trick that king and his people and turn them against him so that they would not receive him; for this purpose they sent a delegation to the king - a thing against the church laws, we are told - which was not recognized nor received: "We shall not receive - they said - any other but our spiritual father who begat<ref>"Begat" or "would beget": in the first case, reference would be to the Nobades, in the second to the Alodaei. It is not clear who is the king to whom the delegation was sent; "Alodaei" has been supplied by the translator, but it is uncertain.</ref> us against by a spiritual generation and whatever his enemies say against him we hold as false". So they rejected and did not receive them. (pp. 203, 204).

[ch.50] [The delegation sent by the Alexandrians to the Alodaei.]

When the Alexandrians learned that the king of the Alodaei had sent a second delegation to the king of the Nobades to send him Longinus, who had instructed him in the faith, then prompted by envious zeal, they sent a delegation to that people to excite them against Longinus and to introduce that ruin and transgression of the ecclesiastical discipline,<ref>The i.e. the Melkite confession.</ref> which they had started and to instruct them in it. Then they prepared a careful and deceiving letter for them in regard to Longinus. They did not fear God and so, moved by envy and hatred, they did not entertain thoughts of Justice; these would have showed to them that it was not according to the fear of God to convey in writing, immediately, before other things convenient to their conversion, what referred to [p. 16] the dissension, quarrels and schisms among Christians. And this to a people, who from error and paganism had asked to turn to Christianity and to learn God's fear. But, since, as aforesaid, their mind was clouded and their foolish intellect<ref> An implicit quotation from Eph. 4: 18 and Rom. 1:21.</ref> was blinded, instead of the fear of God, they laboured to set for them, as first basis, offensive enmity, by construing a letter against Longinus and sending it by means of two bishops - among those they had created contrary to the church laws - and of other people.

Archeology (Jebel Moya):

The Site of Jebel Moya, located in the Southern Gezira highlights many of the Nilotic cultural affinities noted above during the Meroitic peroiod, and also showed evicdece of trade and interaction with the cultures of the Meroitic spheres, as well as the Napatan one. There may have also been a trading station in the area just east of this site, near the modern day town of Sennar, and in ancient historical records, is mentioned as a district called "Cyeneum", a place where the Axumites would trade and attain ivory. Making the people if Jebel Moya an integral part of Meoirtic trade relations down the Nile & across the Batuana and Eastern Desert. The ancestors of the Dinka, and possibly western nilotes as a whole may be associated with the agro pastoral groups of the Southern Gezira, & Butana region. Who existed in the area there from 100bc-500ad. However, it should be noted that occupation of these Nilotic like groups only began around the last century bc (100ad), which we can probably infer an arrival from more northerly areas before this period. It could be assumed that the nilotes arrived in this area from the North to North West after their migrations from the Wadi Howar Diaspora. However after this period, it could be assumed that the populations started to migrate south again. We see an end of the pastoral culture during the beginging and early stages of the formation of the Christian Alodian kingdom, which is 1st mentioned around this time (6th century A.D). The people living the Southern Gezira area at this time practiced semi nomadic cattle pastoralism, & as well as dental evulsion, which are characteristic of western nilotic societies.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231903164_Prehistory_in_the_upper_Nile_Basin

(Quote)

As the proto-Nilotes or their immediate ancestors are most likely to have obtained their domesticates from the north, a case can be made for a homeland immediately south of the Eastern Sudanic block, perhaps on the White Nile lake that extended north of the Bahr el Ghazal confluence during the period in question (Wickens, 1975, p. 62, fig. 5). (Of possible relevance here is the characteristically Nilotic trait of evulsion of lower incisors practised by some of the population of Jebel Moya [Addison, 1949, pp. 53-5]. Jebel Moya is only 270 km south of Khartoum and within the orbit of Meroe, though occupation is known to go back at least into the late third millennium bc [Clark and Stemler, 1975]). Adaptation of economic strategies to allow pastoralist exploitation of the wetland savannah, especially east of the White Nile, is surely a critical but as yet archaeologically undocumented factor in the first phase of Nilotic expansion into an area previously inhabited, if at all, only by hunter-gatherers. The linguistic evidence does not appear inconsistent with the concept of a dialect chain within which from north to south the Western, Eastern and Southern branches were beginning to diversify. Such a reconstruction differs only in emphasis from that of Ehret and his colleagues, but it avoids the need to postulate a not easily explicable reflux movement of proto-Western Nilotes back to the north. Moreover the archaeological evidence seems to favour a late survival of hunter-gatherers in the drier savannah of the extreme southeastern Sudan

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4856204

Quote:

The southern Gezira, therefore, formed a dynamic zone of interaction on the Meroitic state's southern frontier, with settled and semi-settled agro-pastoralists, at least one Meroitic station at Sennar, and a large pastoral occupation at Jebel Moya. The peoples were likely an integral component of the Meroitic trade network both down the Nile and--if the interpretation of the Periplus identifying Sennar is correct--across the Butana and the Eastern Desert, including the southern Atbai and Aksum, to the Red Sea. The social configuration at this time included the emergence of an elite at Jebel Moya, detectable in the mortuary realm through the spatial neighbourhood in its northeast sector. Differences in social organisation between these communities and those in the Meroitic political heartland can be elucidated by briefly outlining the mortuary behaviour exhibited at non-elite cemeteries in the Shendi Reach

Quote:

Finally, Period 3 is from the first century BC until the mid first millennium AD, and it is to this pastoral phase that the vast majority of the burials are assigned (Brass and Schwenniger 2013).

(Page 22)

Quote:

Archaeological studies suggest a Nilotic presence in central Sudan many centuries ago. During the Meroitic period (c. 300 B.c.E. to 300 A.D.) the plains between the White Nile and its tributaries were rich corn-growing regions; the most fertile was that between the Blue and White Niles, the Gezira. It was covered with a dense forest of mimosa thorn and plentiful in rain. In this region 270 kilometers south of present-day Khartoum (at the confluence of the Blue and White Niles) there is archaeological evidence at Jebel Moya (in the center of the Gezira) of the Nilotic trait of evulsion of the lower teeth practiced by 12.8 pereent of the males and 18.1 percent of the females. Evul-sion, or removal of the lower incisors and sometimes of the upper is a custom practiced in the ethnographic present overwhelmingly by all the Western Nilotic people (Dinka, Nuer, Shilluk, etc.). Lipstuds, another Jebel Moya trait, are also worn by some Nilotic peoples today! More persuasive are a number of ar-chacological studies from the Southern Sudan strongly supporting the view that the Dinka culture was not indigenous to this region.

Earliest Mentions

Kings Expedition:

The earliest of mention of people who were likely ancestors of the nilotes are from a writing on an expedition to explore south of the Alodian territory (which at the time seemed to have been limited to the northern Gezira) along the white nile. This expedition took place during the 10th century and the king was said to run into people who "reared cattle" in their underground like settlements. This sounds somewhat reminiscent of nilotes as far as cattle rearing goes, and also considering the migration southwards from Jebel Moya by 500ad, on top of the fact that their may have not been many other people we may have as "options" to designate the identity of these people to besides western nilotes, considering the time perdion and also who would be living south of Alodia along the white nile at that time. I believe a case can be made & if true, supports to the idea pushed by Beswick in her book "Sudan's Blood Memory" that nilotes originated in Central Sudan, as it would add the list of attestations of people living in the gezira (between teh white and blue niles) of nilotic or Nilotic like people.

quote:

Finally, it is worth comparing this picture of conditions south of the Nile confluence in the first century AD with those existing nine centuries later when Ibn Selim el Aswani, the Moslem ambassador and historian of Nubia, visited Soba, capital of the V Notes Christian Nubian kingdom of Alwa close to the junction of the two rivers. Then (c. 976 AD), Alwa's territory and sphere of influence appears, as in Meroitic times, to have been limited to the northern Gezira. A king of Alwa who explored farther south could only find men living with their cattle in cave-like dwellings underground or below ground level - possibly a description of rock shelters with sunken floors (Troupeau, 1954). Ibn Selim could obtain no information about the sources of either the White or the Blue Nile; the Green Nile as he calls it. The upper reaches of both rivers were inaccessible because of tribal tensions.

Cyeneum:

One of the earliest of mentions of people who could've possibly bee ancestral to the Western Nilotes are the people of Cyenuem during the early 1st millennium C.E. Information of this place is very vague, however it is assumed by some that this place was near modern day Sennar in Sudan. It was mentioned as an important district area of ivory trade to the Axumites in the "Periplus of the Erythraean Sea". Maps of the Horn of Africa during the 1st century A.D place the location in Southern Sudan however. This possibly could've been early Western Nilotic peoples who we know traded with the kingdom of Meroe, and were also pastoralist at the site of Jebel Moya, located just west of Sennar from the dates of 100bc - 500 A.D. Other than this mention in association with Axum, we also know of contact that the area of the Southern Gezira (where Cyeneum may have been located) had contacts with the Kingdom of Meroe, as this can be seen through the archeological data from around the same time period. During the Roman expedition mentioned by Seneca in the 1st century C.E to find the source of the nile, the expiditioners made a stop to Meore, where the Meroitic elites sent a letter of request for assistance to the elites of the Southern Gezira (Cyeneum?). Who would then lead them the the Sudd swamp lands in modern day South Sudan.

Quote:

From that place to the city of the people called Auxumites there is a five days' journey more; to that place all the ivory is brought from the country beyond the Nile through the district called Cyeneum, and thence to Adulis.

- Periplus of the Erythraean

Sea, $4

Quote:

They used formerly to anchor at the very head of the bay, by an island called Diodorus, close to the shore, which could be reached on foot from the land; by which means the barbarous natives attacked the island. Opposite Mountain Island, on the mainland twenty stadia from shore, lies Adulis, a fair-sized village, from which there is a three-days' journey to Coloe, an inland town and the first market for ivory. From that place to the city of the people called Auxumites there is a five days' journey more; to that place all the ivory is brought from the country beyond the Nile through the district called Cyeneum, and thence to Adulis. Practically the whole number of elephants and rhinoceros that are killed live in the places inland, although at rare intervals they are hunted on the seacoast even near Adulis. Before the harbor of that market-town, out at sea on the right hand, there lie a great many little sandy islands called Alalai, yielding tortoise-shell, which is brought to market there by the Fish-Eaters

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4856204

Quote:

Quote:

The increase in direct Roman commercial interest in the Red Sea coast arose after Augustus Caesar established control over Egypt in AD 31; the aim was to reduce, or take control of, the trade monopoly from the Arabian Peninsula states. The trading routes encompassed the southern Red Sea as far south as East Africa and round the Arabian Peninsula through to India. The Periplus Maris Erythraei records that ivory was brought to the port of Adulis via Aksum and its hinterland. African ivory was regarded as being of superior quality to its Indian counterpart. The Periplus also states that "all the ivory from beyond the Nile [is brought to Aksum] through the district called Kueneion, and thence to Adouli [Adulis] (Huntingford 1980). Kueneion has been hypothesised to be in the area of ancient Sennar, c. 350 km east of Aksum (Kirwan 1972, p. 166; Phillips 1997, pp. 450-451). The mention of the area beyond the Nile' should not be regarded as odd, as the Roman Emperor Nero sent an expedition to explore the origins of the Nile and the possibility of trade further up the Nile; this expedition ventured south from the branching of the Nile near Khartoum and from the southern Gezira to the start of the Sudd swamplands. More evidence though is required to substantiate or disprove this old hypothesis locating Kueneion on the banks of the Blue Nile.

Quote

A combination of the historical influence of Egyptology on Meroitic studies, the northern concentration of early rescue expeditions, and a focus on the main political and religious centres of the Nilotic-oriented early civilisations, has meant that little large-scale, systematic attention has been paid to the southern and southeastern frontiers outside the confines of the Nile (Ahmed 1984; Bradley 1992; Brass and Schwenniger 2013; Kleppe 1986; Manzo 2012b; Marks and Mohammed-Ali 1991; Sadr 1991). Supporting a model of a variety of socio-economic cultures in a mosaic of trade and political alliances in the frontier zone of the southern Gezira is the account by the Roman writer Seneca (Nat. Quest. VI 8, 3) of the first century AD Roman Emperor Nero's expedition to trace the Nile upstream. The expedition's likely purpose was to investigate new trading sources for the wider Roman Egypt-Meroitic state-Indian Ocean trade network in operation at this time. Seneca relates that the Meroitic ruler issued a letter requesting the local elites to grant unspecified assistance to the expedition's members (Welsby 1996). Therefore, there appears to be textual data indicating the Meroitic elite's engagement with the communities to the south; the evidence for contact to the southwest has been much more contentious.

The" Damadim":

Another mention which may be of relevance to the Nilotic peoples and likely the ancestors of the Dinka's are the "Damadim". The “Damadim” were mentioned as a group of blacks (possibly Western Nilotes) living to the southwest of Alodia, & possibly the Southern Gezira by many medieval Arab writers during the 13th century. Sources are vague, but are mostly interpreted to suggest a presence of these people in the Bahr al Ghazal & Sobat area of South Sudan bordering on the modern country of Sudan, while some others suggesting presence also in the Southern Gezira of modern Sudan. Namely Stephanie Beswick, who places the location of the Dinka’s somewhere along the white Nile, in the Gezira plains region. These people could've likely been the descendants of populations at sites like Jebel Moya, living in the Southern Gezira just a few centuries earlier. Then later traveling back north to conquer the Christian Kingdom of Alodia & sacking it's capital city Soba.

http://www.medievalnubia.info/dev/index.php/Al-Harrani

(Page 449)

Quote: (Al Harrani)

... The country of the Damādim lies along the Nile above the country of the Zanj. It is densely populated. The sūdān always go on raids to this country, killing and plundering. The Damādim do not care about their religions (adyāni-him). In their country there are many giraffes. It is in this country that the Nile bifurcates, one branch flowing to Egypt, and the other towards the Zanj country. (MS Gotha, fols. 30 v - 31 v; MC 1126 v - 1127 r).

http://www.medievalnubia.info/dev/index.php/Ibn_Sa%27id_al-Maghribi

(Page 400)

Quote: (Ibn Sa’id al-Maghribi)

... Among the towns of the Blacks (as-sūdān) located in this fourth Section (juzʾ) there is Dumduma, whence the Damādim people set out against the Nūba and the Ḥabasha in the year 617 H. [1220 A.D.], at the time when the Tatars (at-Ṭaṭar) invaded Persia. For this reason the Damādim are called "the Tatars of the sūdān". The aforesaid town is located at Long. 54° 20' Lat. 9° 30'.

(Page 24)

Quote:

“These accounts make clear the Damadim were also based in the southern Gezira as well as near the Sobat and that they waged war with their neighbors on both the Blue and White Niles”

The Conquest of Soba: "Tartars of Sudan"

Sometime around the 13th century this group invaded Alodia & the Habesha (Axum?). It was mentioned that “the Sudan:” (Alodian Kingdom?) would always go on raids into their country, killing, raiding, & plundering. This possibly could’ve triggered the the Damadim invasion & conquest that would soon follow.

http://www.medievalnubia.info/dev/index.php/Al-Harrani

(Page 449)

Quote:

... The country of the Damādim lies along the Nile above the country of the Zanj. It is densely populated. The sūdān always go on raids to this country, killing and plundering. The Damādim do not care about their religions (adyāni-him). In their country there are many giraffes. It is in this country that the Nile bifurcates, one branch flowing to Egypt, and the other towards the Zanj country. (MS Gotha, fols. 30 v - 31 v; MC 1126 v - 1127 r).

They sacked Alodia’s capital city of Soba and occupied the area around 1220 [A.D.] During this same time, the attack of the Tarters against the Moselems of Persia took place. For this, the Damadim were called the “Tarters of Sudan”.

http://www.medievalnubia.info/dev/index.php/Ibn_Sa%27id_al-Maghribi

(Page 400)

Quote:

... Among the towns of the Blacks (as-sūdān) located in this fourth Section (juzʾ) there is Dumduma, whence the Damādim people set out against the Nūba and the Ḥabasha in the year 617 H. [1220 A.D.], at the time when the Tatars (at-Ṭaṭar) invaded Persia. For this reason the Damādim are called "the Tatars of the sūdān". The aforesaid town is located at Long. 54° 20' Lat. 9° 30'.

http://www.medievalnubia.info/dev/index.php/Abu-l-Fida%27

(Page 465)

Quote:

Another nation are the Damādim who live on the Nile above the Zanj, and are "the Tartars (at-Tatar) of the Blacks (Sūdān)". They (the Damādim) waged war against them (the Zanj ?)<ref>Possibly the Nūba or other peoples may be meant here, but, grammatically, the adverb refers to the Zanj.</ref> and killed many, as it happened between the Tartars and the Moslems. They do not care about their religion (adyān); they have idols (awthān) and different manners. In their countries there are giraffes. In the land of the Damādim the Nile divides, one branch flowing towards Egypt, the other to the Zanj. (Beirut I, pp. 119 - 120).

Archeological record shows evidence of the destruction of Soba around this time, possibly related to the conquest of the Damadim. Two of Soba’s largest Churches were destroyed, royal burial sites were looted. One church was also used as a residence for a certain period of time but was later restored.

(Page 115)

Quote:

The intrusion of African tribes into Nubia around 1220

For the first half of the 13th century, there are only a few reports, except for some notes from Abu 1-Fida' and Andalusĩ. They report that the "Damadim" overran Nubia and neighboring countries. The identity of the Damadim is unclear. In Soba, archaeologically, it is evident for the early 13th century that two of the largest churches were destroyed, and the local burial sites, probably of high ecclesiastical dignitaries, were looted. Apparently, a church was used as a residence temporarily and restored as a church after a certain time. This suggests a temporary occupation of Soba by foreign troops and could be related to the conquests by the Damadim.

Andalus, Gugrafyi, OrS: 399-416. Andalus dates the attack of the Damadim on the Nubians and Abyssinians to 1220 and mentions that they were referred to as the "Tatars of the Blacks" due to their simultaneous invasion with the Mongols in Persia, see OrS: 400. Andalusi is often imprecise in terms of locations, as seen in references to the locations of Dongola and Alwa, see OrS: 404-405. Abã I-Fidi' also mentions the Damadim in Tagwim ai-Buidān (Arabic: "Measurement of Lands") and the German term "Dandama" as the place of origin of the Damadim, see OrS: 463. In Multasar ad-dial, Abd I-Fida' mentions the Damadim as the "Tatars of the Blacks" and states that the Nile divides in their land. They have no religion, see OrS: 465. The geographical indications point to a region in South Sudan in the area of the Nile tributaries, see Magrzi. Bifaf, OrS: 593, which refers to a branch of the Nile as the "River of the Damadim." This could indicate the Bahr al-Ghazül (Arabic: "River of the Gazelles," a tributary of the Nile in southwestern Sudan), as also noted by Umarf, see OrS: 513-514.

Vantini 1985: 230-231 suggests the Luo or Dinka as possible tribes that shifted their residence in the Middle Ages. An exact identification remains challenging. Arabic historians find it difficult to provide reliable information on the names and locations of Sudanese tribes, see also Vantini 1981: 162 and 1985: 229-231.

Welsby and Daniels 1991: 9.

Welsby 1990: 13.

Cyril III is also known as Ibn Lagläq, see Burmester 1974: 177.

Migrations South

However, this conquest wouldn’t last very long, later we see that in the following centuries a migration southwards of theses tribes. An important thing to note around this time (the Medieval Period), is that we see the spread and expansion of many Western Nilotic groups, mostly from the northern Southern Sudan & Central Sudanese region, into the rest of South Sudan & East Africa. These mostly include the Dinka-Nuer & Luo groups. Many of these expansions coincided with the fall of the Christian Nubian Kingdom of Alwa (Alodia).

(The Decline of Alodia: Slavery in Nubia)

Many reasons for these Southward migrations of the Dinka & their western Nilotic cousins living directly south of them would’ve occurred for a multitude of reasons. The Dinkas during this time would’ve mostly lived throughout the Kingdom of Alodia, I the Gezira region. Soon after their conquest and occupation of Alodia, they started migrating southwards. Bedouin tribes soon started to invade from the Northern reaches, running slave raids in the regions. Which unfortunately wasn’t a new thing for Alodia, as there are mentions going back to the 6th century A.D. This event, plus major droughts are thought to be some of the reason for Alodia’s rapid decline, & as well as why the ancestors of the Dinka migrated south.

As reported by Stephen Beswick, there were negative Muslim attitudes against African tribes living in the areas of the Central & Southern Gezira.

(Page 30)

Quote:

Early evidence of contempt and negative Muslim attitudes towards non-Islamic peoples of the southern and central Gezira is illuminated by the fourteenth century geographer, Abi Talib as-Sufi Ad-Dimishqi: "Beyond the Alwa country there is a land inhabited by a race of Sudan who go naked like the Zanj and who are like animals because of their stupidity; they profess no religion."

Slave raids in Alodia were very common, as they were usually in war with their neighboring Nubian Kingdom (Makuria), and at times the Makurians would run slave raids within Alodia. “Athiopian” slave traders were very common during this area, & it is also possible that Alodia itself may have been a slave trading state, as their King was even allowed to enslave his own subjects. Some of the earliest mentions of Alodia even report about the sale of an 12 year old Alodian salve girl in Egypt by the name of “Atalous”. She was even said to have been possibly sold off by her own rulers. In later centuries however, Alodia’s populations seem’s to have suffered a rapid decline due to slave trading from neighboring Makuria, and possibly incoming Arab tribes. It is also important to mention that around this time (6th Century A.D.), many of the ancestral peoples of Western Nilotic peoples would’ve occupied much of the Central & Southern Gezira. Not to indicate the Atalous was a western Nilote, but however this is something to keep in mind.

Account of Atalous:

(Page 149)

Quote:

…documents the sale of a black slave-girl named Atalous, an ethnic loan who was approximately twelve years old. Both Kirwan (1935: 57-62, esp. p. 62 n. 11; 1957: 37-41, esp. p. 41) and Mon. neret de Villard (1938: 68 and n. 4) recognized this text as an early reference to the Nubian kingdom of Alodia (Alwah), and their conclusion seems warranted. The Svriac text of the church historian, John of Ephesus, records that bishop Longinus con- verted this kingdom to Monophysite Christianity in A.D. 580, a date not far removed from that of our papyrus. At that time Alodia was in conflict with its northern neighbor, Makuria; and the troubled times may have facilitated the activities of the slavers who uprooted Atalous from her home. Some centuries later Alodia seems to have suffered a decline in population due to slave-raiding from Makuria (Yûsuf Fad Hasan 1973: 130- 131). On the other hand, Adams (1977: 471) inferred from information provided by Arabic sources that Alodia might itself have been "primarily a slave-trading state"; and since the geographer al-Magrizì, writing in the 14th century A.D., recorded that the king of Alodia had the right to enslave his subjects (Yâsuf Fadl Hasan 1973: 47), it may be that Atalous had been sold off by her own rulers.

The account later reports that this girl was purchased to a women by the name of “Aurelia Isidora”. A resident of Hermopolis Magna in Egypt.

She was also likely a women of high standing, however the there was no mentions of her having a husband, possibly meaning that she was unmarried or widowed at the time. The sellers however, both named “Pathermuthis” and “Anatolios”, seem to have been people in lesser standing. They beared no Roman names or respectful epithets (titles). They received Atalous from “Ethiopian” (Alodia or Makuria: Nubian) slave traders. The slavers mentioned seem to have played more as middle men if anything. The phrase “Athiopian slavers” has been said to reference slaves from the Meroitic territory according to some sources. However, the text are not explicit enough on this. She was eventually given a Christian name “ Eutykhia”, which translates to “lucky” in the Greek language. This possibly indicates her baptism into Christianity. However, unfortunately, not much is known beyond this.

As mentioned earlier, in later centuries the Alodian populations suffered a severe population decrease because of frequent slave raids ran by Arabs & possibly other Nubian kingdoms such as the Makurians. Descriptions of the slave raids on Alodia were described as the following…

Accounts of later slavery on the residents of Alodia:

(Page 30)

Quote:

Evidently these non-Islamic peoples of different cultures and religions in the Gezira were viewed as fair game for slaving expeditions for centuries; a twelfth century geographer, Tahir al Marwazi, wrote: Cunning merchants visit the places [of those Zanj] to kidnap their children and boys. The merchants go out to the grazing lands [of the Zanj] and hide in swamps covered with trees, carrying with them dry dates which they throw in the playground of the boys, who scramble to pick them up, find them good and ask for more. On the next day, the merchants throw the dates to them in a place further than the one of the previous day and so continue to go further. The boys follow . and when they are [sufficiently] far away from the homes of their fathers, the merchants rush on them, kidnap them and take them to their home countries.*

These historic attestations run consistent with Dinka oral traditions claiming that slave raids were ran on the forefathers of the Dinka tribe. However, another thing to mention that may have initiated the migration south of the Dinka’s asserted by Stephenie Beswick in her book “Sudan’s Blood Memory”, was drought. She states that the Gezira region of Alodia may have also been suffering famine & drought during the years of the early 13th century, as stated in the Dinka oral tradition. She states that scholars report that in Eastern Africa, severe drought during this period, & that it was also recorded that in the year 1201 A.D. Egypt suffered a famine that killed a third of their population. An important switch during this period also occured. Around this time, we had western nilotic group adopting the Zebu cattle, which would help them in their later rapid expansions into much of Eastern Africa during the later centuries, primarily due to this cattle ability ti be able to survive more arid climates.

(Page 30)

Quote:

Along with Dinka oral histories of slave raids when their forefathers lived in central Sudan are traditions of drought during this era. Supporting evidence of severe ecological stress is offered by various scholars who note that the climate from the seventh to the twelfth centuries was fairly stable. After this time however, severe droughts plagued Eastern Africa at intervals from the thirteenth to the late fifteenth centuries. In 1201, for example, famine killed one third of Egypt's population. Thus, in the thirteenth century famine and war struck simultaneously in the Gezira. Thus, on the basis of available evidence, it appears that the forefathers of the Dinka, who formed part of the slaving classes in the region, began to migrate southwest out of the Gezira in or after the thirteenth century--a date coinciding with..

These text make it clear that the oral tradition run constant with recorded events of droughts and other catastrophic events during this time period. These provide backing for these oral traditions recited by the Dinka’s.

Fighting with the Funj:

On the migrations south after the fall of the Alodia kingdom, many Dinka clans ran into various peoples, and one of these were the “Funj”. They met with these people somewhere likely around the Nile Sobat region. In northern South Sudan. They fought with the Funj & displaced them up north.

Who were the Funj?

Founded in 1504 by the early Sultan Amara Dunqas, the Funj Sultanate was a monarchy founded by the Funj people in what is now Sudan & western Ethiopia. They quickly converted to islam shortly after their establishment of their kingdom. Happening once they & or along side with incoming Bedouin tribes who overran Nubia after the fall of the medieval Nubian era. Their sultanate reached its peak during the 17th century, but then shortly after declined and fell during the 18th & 19th century. And in 1821, the last sultan (Badi vii) surrendered to the Ottoman Egyptian invasion without a fight.

The funj peoples may have started off as a group originally from Southern Sudan. Many historical documents and oral traditions suggested a more Southern origin of these peoples. Some documents claim that they were “Pagans from the primitive southern swamps”. Other sources suggest that they were affiliated with some western nilotic tribes like the Shilluk and Dinka, while others also suggest that they were Nubians of the Alodian Empire who went south after the fall of Alodia and then came back.

Locations of the Early Funj:

(Page 32)

Quote:

With the fall of the kingdom of Alwa in the thirteenth century and the beginning of the great Dinka migrations south, many clans arrived at the junction of the Sobat and Nile Rivers and displaced and warred with, and absorbed, a new people. On the evidence of their settlement mounds, pottery and construction in red brick, this particular culture was the "Fun;" who represented the far-southern remnants of an older culture of the Gezira. These folk were also members of the central Sudanese cultural tradition that included ancient Meroe and medieval Nubia and thus they were, in reality, ethnically Nubian. Dunghol Dinka, Cok Kuek Ywai who resides in this former Funj region, notes that even today there are non-Dinka pots to be found in his homeland: "According to my grandfather ... we met the Funj going southwards and fought with them. Today around Renk there are artifacts that used to belong to the Funj. When you dig in the ground you step on pots made of mud that were burned and do not perish; these are Funj pots. Every section of the Dinka has its own decoration and its own size, and we always know our own pots."

Battles:

(Page 32)

Quote:

Although these wars took place centuries ago, the memory of them has been preserved in Dinka oral histories. Abialang Dinka Musa Ajak Liol states: "When we killed the Funj the women made pots and cut off the heads of the Funj and put them in pots and buried [them]." A similar oral history is remembered by Eastern Ngok Dinka, Simon Ayuel Deng: "When we moved east of the Nile we found Funj and we fought them. We overtook this place and took their land and came and settled in our present location. We pushed the Funj to the Blue Nile."

Funj & Nilote relations:

(Page 25)

Quote:

Another manuscript collected by MacMichael refers to the medieval period of the Funj Kingdom of Sennar (1504-1821) in the Gezira. Here there is evidence that the Dinka and Shilluk remained a strong presence within the kingdom's periphery. Dekin, an early Funj sultan (1562-1577) claimed that his brothers were "Shilluk, Dinka and Ibrahim. "23 The nineteenth-century genealogies of the Hameg, the successors to the Funj sultans at Jebel Gule in the Gezira, mention Shilluk, Dinka, and Kira (the ruling elite of the Sultanate of Dar Fur in the far west) as having a common ancestor with the Funj, the ruling elite of the Kingdom of Sinnar. This ruling elite was of Nubian ancestry, 24

After these many battles with the Funj, they were eventually pushed up North and eventually establish the Funj sultanate at Sennar. The Dinka tribes from this point began to settle the area, and migrate to the West and the South to occupy their modern territories.

South Sudan:

Throughout much of the 15th - 18th centuries, we see the migration and expansion of the Dinka tribe into much of what is now South Sudan. These expansions have been supported by a number of archeological studies, and have also been documented through the Dinka oral traditions. They conquered many smaller tribes and quickly dominated the area. And here, they are illustrated below in a map from the book "Sudan's Blood Memory" by Stephanie Beswick. Whose book made a major contribution to the writing of this article. These migrations look to have been draw from a migration after the sacking of Alodia's capital of Soba. And from these areas, we see a Dinka expansion into much of their current territories in South Sudan.

Map from Stephanie Beswicks "Sudan's Blood Memory":

Wars with the Shilluk

Another people that the Dinka would war with were the Shilluk. During the 17th century, oral accounts from the Shilluk would describe an intense military pressure from the North East frontier to what they'd describes as "hordes of Dinka". These Dinka would engage in many wars with them. However it is also mentioned that at this time, the Shilluk and Dinka had united against the expanding kingdom of Sinnar (Funj). And oral accounts report of the Northern Dinka clans successfully invading the Funj kingdom. However, things weren't all that great fro the Dinka, later wars with the Shilluk would prove devastating for the Dinka when the Shilluk kingdom had expanded, & grown in power through trade with neighboring sudanese kingdoms and states, and as well as the acquisition of more effective weapons through trade.

Description by the Shilluk:

(Page 34)

In the seventeenth century, however, Shilluk oral histories record that they came under severe military pressure on their northeastern frontier. In this era an increased number of Dinka clan groups, described by the Shilluk as "hordes," fled southwest out of the Gezira away from the rapidly expanding kingdom of Sinnar. Weather patterns had reverted from the previous centuries and this region now witnessed severe droughts and, according to the Funj Chronice, hit the Gezira during the reign of Sultan Badi I's nephew, Unsa walad Nasir. "It was he during whose reign there appeared the year of 'Umm Lahm.' That was a year of famine, and of a plague of smallpox. It is said that the virulence of the famine was such that people ate dogs." In this same time period another source for history is the Tabagat which notes drought and the death of a shaykh: "He passed away at the age of 91 in the year 1094/1682-83 and in 1095/1684 'Umm Lahm' began." The Tabagat also lists droughts in 1686-87 and 1696-97.13 Thus, drought in the latter seventeenth century is well documented in Sudan; it appears, once again, that more Dinka clans were forced to flee the Gezira both because of drought and war in search of their extended families at the junction of the Nile and Sobat Rivers and beyond.

As the Shilluk forcibly tried to stop these new Dinka migrants from settling in their land, violent and bitter wars broke out.

Defeat of the Funj

(Page 34-35)

Quote:

Ironically, around this time in the Gezira some Dinka clan groups and the Shilluk actually united when Sinnar annexed the seventeenth-cen-tury successor state to the fallen Nubian kingdom of Alwa, Fazugli, to its south. This kingdom lay beyond the borders of the southern Gezira in what is now modern-day Ethiopia and the invading Funj Sultanate faced intervention from these Nilotes who, it was claimed, were formidable fight-ers. Their "citizenry at arms" far outnumbered the small professional armies of the Funj. Oral histories collected by a British administrator claim that the Dinka leader, Aiwel Longar, invaded the Funj Empire and that he and his son, Akwaj Shokab (Cakab), pursued the enemy as far as the Shidra Mahi Bey. This correlates with the Dinka oral histories of wars with the Funj, and the belief that "The Padang [Dinka] went from Nasir up to the. horders of Ethiopia. We were led from west to east by Ayuel (Aiwel) Longar, leader of all the Abialang.

Defeat of the Dinka:

(Page 35-36)

Quote:

Throughout the reigns of Shilluk kings Reth Boc (1650-60), Reth Abudok (1660-70), and Reth Tokot (1670-90), these Nilotes were still at war with the Dinka as the latter struggled to cross the Nile from west to east, southwest of the Shilluk territory. This steady population movement compounded competition for available resources and intensified ethnic stress. Soon after this period, however, the balance of military power shifted unequivocally in favor of the Shilluk when the latter made a trade alliance with the Muslim Nuban king of Tagali giving the former access to a reliable source of iron for weapons. At this point the Shilluk became even more politically centralized because of an extensive trade network which developed and allowed the war against the expanding Dinka to be resolved in favor of the former. 18

Thus, although the Dinka were by now numerically stronger than the Shilluk, the latter predominated over this region of the Nile/Sobat confluence ruling as far north as El Ais. By 1799 traveler W. G. Browne observed that the Shilluk had dominion of the White Nile and conducted a "ferry" service. In the meantime Shilluk traditions recount that after numerous wars the Funj moved north of the Sobat. The leader of the Dinka, on the other hand, Dengdit, retreated to its southern banks. As late as the early Egyptian colonial period (1821) Dinka/Shilluk wars continued to erupt particularly during the reign of the Shilluk Reth Akwot (1825-35).

Another battle with the "Dinka hordes"

represented the last large Dinka

migration from west to east across the Shilluk country to the eastern banks of the Nile. At this juncture, those Dinka living on the right (east) bank of the lower Sobat river had been driven inland by the Shilluk. During this period it is remembered that every Shilluk at that time had a Dinka slave girl and a Dinka cow from the booty of Reth Akwot.!'

From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries Dinka clan groups had increased on the eastern banks of the Nile as well as south of the Sobat and the land had rapidly become overpopulated. They were unable to mi-grill east because of tsetse Ay?0 Nor could they move north because of the Shilluk or northeast because of the Funj Sultanate, nor return west because of the fear of constant droughts. Thus, many now forged further south up the Nile, only to be embroiled in more conflict.

Among some of the earlier or previous inhabitants of much of the land that they had expanded to in South Sudan, one of these people were called the “Luel”. These people are of important because they may represent a earlier, and more indigenous stock of the Southern Sudanese. Their identity is a rather complex one however. They are said to have been a mix between an earlier more aboriginal South Sudanese people (central and or East African hunter gatherer like?) and as well as the Western Nilotic Luo. They may have been mixed with a Duo group that expanded into the North Western fringes of Southern Sudan early. They inhabited the area in what is now in South Sudan's Warrap state, which is now mostly inhabited by the Western Twich Dinka.

The Nuer Relations & Expansion

The Nuer expansion was one of the greatest set backs of the Dinka tribe, it occurred during the 19th century and primarily was the expansion of Nuer Groups into former Dinka territories. They cut into the Dinka territories in creating a divide between the Bor and Padang Dinka subgroups, absorbing many Dinka clans un the process. The Nuer Lou section are notable in this aspect because it has been reported that up to 70% of their population was of former Dinka origin. This expansion however was stoped during the colonial period.

(Page 164)

Quote:

Most scholars of the modern-day Sudan are aware that there has been a long historical conflict between the Dinka and their closely related Nilotic neighbors, the Nuer. However, the relationship between these two is an enduring mystery, particularly as the Nuer today comprise approximately 70 percent of peoples of former Dinka origin. For example, Evans-Pritchard estimated that as much as 75 percent of the Lou Nuer were of Dinka de-scent. Yet, the question of the original forefathers of the Nuer is still open to debate. Even the Dinka and the Nuer do not agree on this issue. Further, the Luo have become very much involved in this discussion because many now believe thar the original Nuer may, in fact, have been one of the several. Luo groups previously resident in the region centuries ago, prior to the Dinka arrival. A subsidiary event also concerns the major body of the Arvor, considered to be closely related to the Nuer.

Much of thir evidence comes from lingine sudies glotroch ronological analysis vilds a separation dare between the Dinka and Nuer at around 85 A.D. Other scholars, however, strongey die agro. Mohamed Riad, for example, suggested that the Nue, like the Shy dik. are of Luo origin.

(Page171)

On the other hand this Nuer expansion also forced many Dinka clans south of their former homelands: Solomon Leek Deng and Abdengokuer Adut note that "We were all along the Nile from Renk down to Bor and it was our area when the Nuer came and fought with us and cut us in two. Now che Nuer are in Waat, Ayot, and Fanjak. When the Nuer came and raided us they took cows, women, and children." An Eastern Iwic Dinka Ding Akol Ding states: "In the early nineteenth century the Nuer pushed the Bor Dinka further south to their present region. We have songs remembering the places we used to live, and today they still have Dinka names, but these areas are now occupied by the Nuer."

Relations with the Nubians

It’s important to note that many linguist try to establish a genetic relation between speakers of the same language families, and for the eastern Sudanics, it is no different. This shared genetic ancestry is likely Dinka or Nilotic related. Throughout the many documented histories of the Sudanese tribes, there are many relations that we see tribes like the Dinka share with the Nubians. The nature of these relations does seem to be rather complex, and fast conclusions should be halted. Things like linguistic relations have been pointed out by multiple linguist, and cases of word borrowing, shared cognate words, and as well as possible absorption (a personal interpretation of mines) can be observed. We also have historic documents that point to a connection of the Nubian peoples of Central Sudan, who may have been part of the Alodia, and Meroitic cultural complex. We see the use of the word or label “Anag” being used to describe the Christian Nubian people of Alodia, and as well as the Dinka.

Linguistic:

(Page 21)

Quote:

Bender lists Nilotic and Nubian as Eastern Sudanic languages and linguistic studies conducted by Robin Thelwall suggest an unexpected degree of similarity in vocabulary between Dinka and the modern linguistic descendant of classical Nubian, Nobiin. Thelwall compared Daju, Nubian, and Dinka and wrote: "The inter Daju-Nubian comparisons give a spread of ten to twenty-five percent. . . . However, the check of Dinka gives one comparison (with Nobiin [the classical language of Nubia]) of twenty-seven percent . . . and this stronger link to Dinka than to Daju implies that it was in close contact with Dinka." In his first interpretation of this linguistic evidence, Thelwall attributed these similaities to a loaning process of historical interaction between speakers of classical Nubian and their Dinka contemporaries.

In the recent past Nubian speakers were widely distributed extending up the Nile as far as modern-day Khartoum and over much of the Gezira.14 The far southern Nubian kingdom was Alwa and, if the subjects of this kingdom spoke classical Nubian, as seems likely, they had at least a millennium in which to interact linguistically with the Dinka who claim to have resided in the same region. Archaeology also supports the Dinka claims of a central Sudanese homeland.

https://openscience.ub.uni-mainz.de/handle/20.500.12030/2112

Quote:

The ancestors shared by the speakers of the extant Nilotic and Surmic languages originally occupied the area through which the Lower Wadi Howar and the Wadi el Milk pass. The Wadi Howar as a whole was part of the diffusion area in which the Eastern Sudanic languages presently spoken in the north acquired the typological features they share with members of other Nilo-Saharan groups, for instance Masalit, Fur and Beria. Interactions in the Central Sudanese Kordofan region during the later southward migrations provided the context in which the other set of typological traits became a characteristic of the Eastern Sudanic languages ancestral to those currently spoken in the south. These contacts most likely also led to language shifts and the absorption of groups speaking typologically different languages.

(Page 253)

Quote:

In 93blku Appuu, an alternate hypothesis was put forward, expanding upon an earlier observation by Robin Thelwall. 36 who, while conducting his own lexicostatistical comparison of Nubian languages with other potential branches of East Sudanic, had first noticed some specific correlations between Nobiin and Dinka (West Nilotic). Going through Nobiin data in $ 111.2 yields at least several phonetically and semantically close matches with West Nilotic, such as:

Additionallv. Nobiin múa "doo" is similar to East Nilotic *.nak-37 and Kaleniin yo:k,38 assuming the possibility of assimilation (*n-> m- before a following labial vowel in Nobin). These parallels. although still sparse. constitute by tar the largest single group of matches between the "ore-Nile Nubian substrate" and a single linguistic familv (Nilotic), making this line of future research seem promising for the future - although they neither conclusively prove the Nilotic nature of this substrate, nor eliminate the possibility of several substrate lavers with different affiliation.

Historical:

https://books.google.com/books?id=LtIDAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

(Page 12)

Quote: (Note that here we see the Funj refer to the Christian Nubian people of Soba as “Anag”)

The FuNG chronicle says that about 1504 A.D. the FuNG and their Arab allies overthrew the Christian "NOBA," otherwise "the 'ANAG, the kings of Sóba and el Kerri," and most of "the NOBA...scattered and fled to Fazoghli and Kordofán®."

https://books.google.com/books?id=LtIDAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

(Page 13)

(Quote)

Western and southern Kordofán, and Dárfür, he speaks of as inhabited by NOBA. He calls the autochthonous DANÁGLA 'ANAG, " and some remnants of them at the present day are called the NOBA." The DINKA are "'ANAG from among the ZING!.

Genetic:

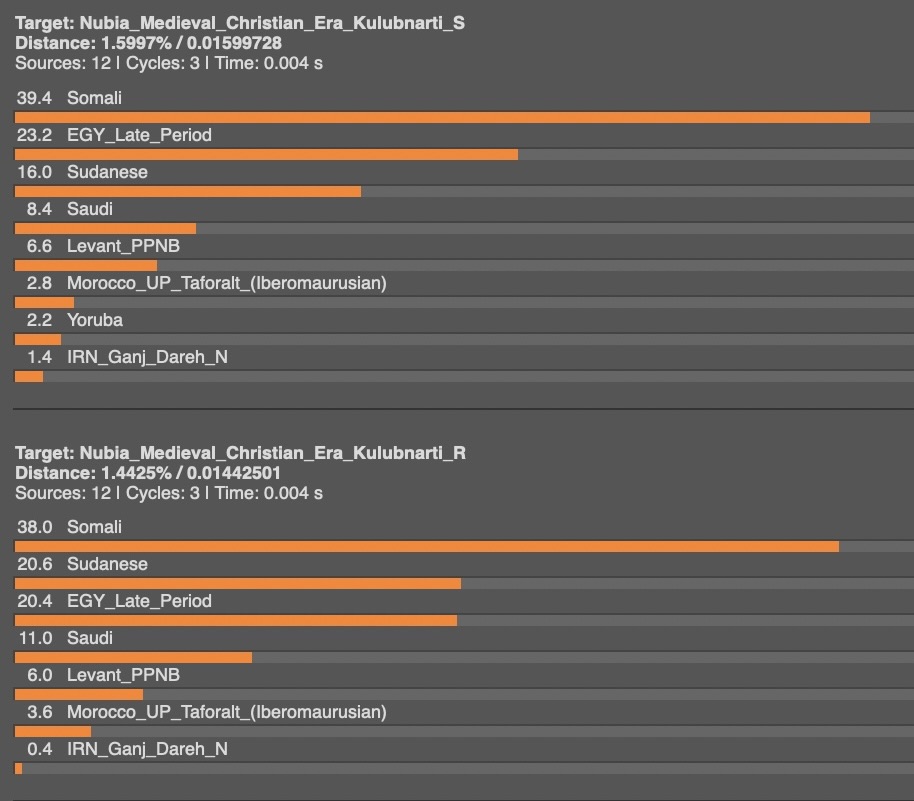

Although ancient dna on the populations of Sudan & South Sudan are sparse, there are some dna & osteological studies that can prove useful in reconstruct the Sudanese past. By looking at the modern dna, in comparison to theories on the spread of Nilo Saharan languages in the Sudan both related to and ancestral to the Dinka people, I was able to breakdown specific components of Nubian dna, being able to associate certain ancestries with historical events (see my video on “Nubian DNA” for more details).

From what we know, North Western Sudan may have been home to various groups both ancestral to the Dinka (& Nilotic people as a whole) and as well as the people of the Nubian Nile Valley who would eventually establish the early foundations for the various empires in the region. The north western region of Sudan, where these Nilo Saharan speakers were located was very important area concerning the neolithization and transition into civilization in Sudan. As there were multiple Nilo Saharan groups (Eastern Sudanic) that cam into the Nubian Nile Valley and helped tremendously, or even founded the different civilization. The 1st of these occurred through and event called “the Wadi Howar Diaspora”, when through the drying of a river in North Western Sudan, many Nilo Sharan groups migrated south, west, and east, and off these groups that migrated east, 1 of those groups were called the “Meroitic” speakers, who would introduce the Meroitic language into Nubia (assuming that the language was Nilo Saharan & not Afro-Asiatic, which is still being debated) and also helped usher in the founding of Civilization by migrating to the Kerma area, and meeting with the previous Cushitic speaking Afro Asiatic people of the area, and founding Nubia’s earliest city state.

Nubian dna can be broken down into 3-4 major components. Which are Cushitic (the 1st layer) from earlier cubistic speaking Afro Asiatic speakers of the Nubian Nile Valley before the migration of the Eastern Sudanic, or Meroitic speakers. After this, the 2nd layer is the Eastern Sudanic, or Meritic dna, which is Nilotic like. This dna came from the event known as the “Wadi Howar Diaspora”, where multiple Eastern Sudanic speakers, both related to, and ancestral to NIlotes lived. All of if not, most of these populations were Nilotic like. Which is why we see this dna within the modern day Nile Valley Nubian, and it is also best represented by Sudan’s Nilo Saharan populations such as the Dinka, Nuer, and Nuba. After this we have a layer of Egyptian DNA, which my Abe explained through the various historical interactions between the Nubians and Egyptians, then, there is a finally layer of Arabian dna, which can be best seen when looking at the YDNA haplogroups of the modern day Nubians.

Conclusion

All of this goes to say that the Dinka have a complex history, still far from being understood to its fullest, poor amounts of excavation, archeological, and dna studies make it hard to get a clear picture, however, this paper is mainly to give a glimpse of a snapshot of what the Dinka, and Nilotic past wast mostly like.

Comments

Post a Comment